*This essay was originally written for Movie Mezzanine.

Few figures in world cinema are as contentious as Mohsen Makhmalbaf. The mere mention of his name conjures responses ranging from admiration to anger and loathing among Iranians who have followed his work for four decades. Makhmalbaf’s films typify the revolution in Iranian cinema that followed the Islamic revolution, and the trajectory of his career reflects the evolution of artists under the new regime. He is at once the archetype of post-revolution Iranian cinema and one of its most rebellious outsiders, and if there ever were an artist whose work could not be separated from his persona, Makhmalbaf would be it. How he went from the prisons of the Shah to exile by the Islamic republic he fought for, and from a pedestrian filmmaker of propaganda to a revered figure on the festival circuit is a lengthy and curious tale. In the summer of 1996, however, Makhmalbaf released two films that provide a neat cross section of his career at a glimpse. Thematically and formally disparate, Gabbeh and A Moment of Innocence share little in common other than the artist helming the director’s chair, but they are significant examples of the director’s varied styles and remarkable range.

Makhmalbaf was one of the founders of Islamic Art and Thought Centre, a powerful cultural organization that produced many of the films made right after the revolution in Iran. Makhmalbaf had a hand in writing, directing, and producing several Islamic films, propagating the political and religious ideologies of the nascent government. His works during this period are artistically negligible, only marginally interesting as time capsules for 1980s Iranian cultural ideology. They can, most charitably, be described as amateurish. With their hawkish tone and a complete lack of understanding of the basics of the cinematic medium, Makhmalbaf used these features as a megaphone through which he screamed propaganda.

Throughout the decade, the suffocating religiosity of Nasuh’s Repentance and sycophantic portrayal of freedom fighters in Boycott gradually yielded way to a more critical look at the turbulent social atmosphere of wartime Iran in Marriage of the Blessed. The latter film exhibits most of Makhmalbaf’s weaknesses as a filmmaker. It’s overzealously directed, ideologically inflexible and blatantly unsubtle. Images, sounds, and dialogue don’t transcend the screen, thus creating an experience that is both dreary and demagogic. Yet, Marriage of the Blessed is significant because it represents a gradual political shift. The Makhmalbaf behind this film has begun to drift apart from the regime he vociferously supported. He is criticizing its treatment of war veterans and its obliviousness to poverty and social inequality.

Similarly, The Peddler and The Cyclist, films about homeless people living on the periphery in Tehran and about Afghan immigrants, respectively, rose to the defence of the lowest rungs of society. Makhmalbaf’s reputation among the secular class didn’t turn since his earliest efforts, but he no longer saw himself as an Islamic filmmaker, but as the filmmaker of the people. Along with his political transition came an evolution of style too, though Makhmalbaf remained technically self-aware, and pronounced in his aesthetics.

The early 1990s Makhmalbaf films are so drastically disparate from his work in the previous decade that they appear as though they were made by someone else. The formal illiteracy of his first few films is completely vanished, replaced by a curiosity in the possibilities of film—as though Makhmalbaf had just discovered the cinematic medium. It is in this period that he directed his most memorable work. Once Upon a Time, Cinema is a playful exploration of Iranian film history that borrowed ideas, imagery, and scenes from the masterpieces of Iranian cinema, but enriched and infused with humour and urgency.

In Hello Cinema, Makhmalbaf’s pseudo-documentary about his casting process, he explores the popularity of cinema in Iran and its sociocultural reach among different classes of people. In the film, he makes no effort to endear himself to the audience, appearing as a stubborn, often unpleasant director with an authoritarian touch. Nevertheless, the final product is a sharp, playful effort that tells us as much about cinema as it does about Makhmalbaf himself.

In retrospect, Hello Cinema is only leading up to the more challenging, complex self-referentiality of A Moment of Innocence, which came a year later in the summer of 1996. That summer, Makhmalbaf premiered two films at European festivals, the other one being Gabbeh, titled after the traditional northern Iranian rug. The latter film is Makhmalbaf’s attempt, the first since A Time for Love, to work in a poetic mode that was prevalent in the country in the 1990s and the early years of the millennium, and a formal and spiritual companion to his subsequent film, Silence.

Then, Makhmalbaf made a clean break with his past, and eventually with Iranian cinema. He travelled across the Middle East and made films in Tajikistan, Afghanistan, Israel, and Georgia. He explored sexuality in ways forbidden under the guidelines of Iranian cinema; he forayed deeper into philosophy and different languages, and remained as politically outspoken as ever, eventually forcing himself into exile.

Today, he’s seen as an apostate and a traitor by the adherents of his early work, but he’s never been fully embraced by secular Iranians either. His shifting politics and opposition to the government is seen less as a consequence of authentic personal beliefs and more as an opportunist move in the direction of current political winds. Makhmalbaf, along with his wife Marzieh Meshkini and his daughters Samira and Hana, built one of the biggest filmmaking dynasties in Iran, but he remains on the outside of the industry looking in today.

Gabbeh and A Moment of Innocence share almost nothing in common. Audience members who saw the two films at their North American premieres—screening two days apart at the Toronto International Film Festival in September 1996—would be forgiven for not noticing they were directed by the same man. If all the twists and turns of Makhmalbaf’s career were put on a spectrum, these films would be on opposite ends, but their asymmetry captures the constantly changing, chameleonic essence of the director’s work.

Gabbeh tells the story of an elderly couple who bring a small but intricate rug to a water stream for washing. The rug, woven by the woman, tells the story of their young love. As they submerge the gabbeh in the water, it comes to life in the form of a young woman who narrates their story. Makhmalbaf pays a loving tribute to the rural handcrafted art forms of his country and the customs of its tribal population.

Makhmalbaf attempted similar approaches to nature and spirituality in A Time for Love and Silence as well, but in all three films, the lyricism and poetry feels inauthentic. Gabbeh is a magical realist film without magic, a stiff, literal take on a whimsical environment The audience is continuously aware of the presence behind the camera. The effort in transferring the mystical beauty of the rug from the surface to the screen is painfully tangible, and exposes Makhmalbaf as a filmmaker for whom poetic poise in cinematic form is forced, not a natural gift.

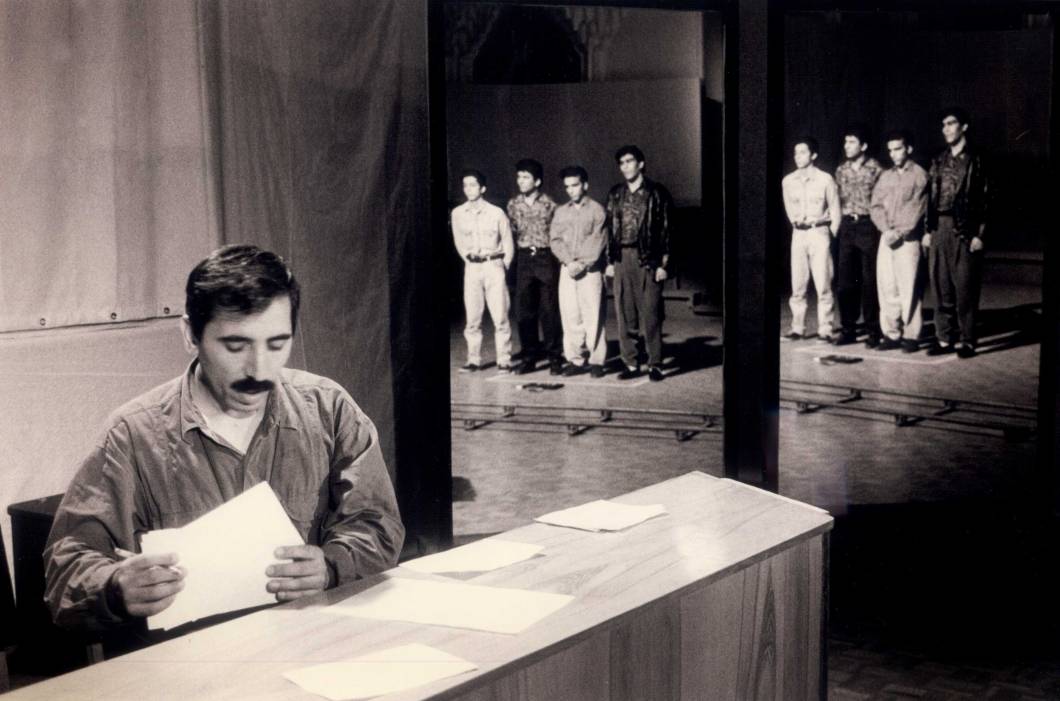

Unlike Gabbeh, a film that feels tediously repetitive even at such a short running time, A Moment of Innocence is all verve and energy. This is Makhmalbaf’s stylistic peak and his most clear-eyed, thoughtful rumination on Iranian society’s post-revolution evolution. Ostensibly about the the casting and pre-production of an autobiographical film, it tells the story of Makhmalbaf’s own arrest by the Shah’s forces after an altercation in which he stabbed a police officer.

The frankness with which Makhmalbaf discusses this hideous moment in his past is refreshing in a country where secrecy is a social value and the smallest hints of negativity are kept hidden from public view. That Makhmalbaf would mention, let alone dissect at length, his stabbing of another man on screen is beyond belief, and needless to say, not endearing.

Helping Makhmalbaf and his assistant in finding the right actor for the role of the young police officer is the officer himself, now in his forties. A significant majority of the film is structured around scenes wherein Makhmalbaf and the officer separately mentor the young actors who are about to portray them in the critical scene of the stabbing. Thus, we are given two diametrically opposing perspectives that have, surprisingly, converged along the years.

Makhmalbaf is thinking out loud, re-evaluating his life and political positions on the screen for everyone to see, and the complexity of his emotions—an amalgam of remorse, arrogance, shame, rationalization, and disbelief—takes the audience on one of the most fascinating character studies in film. He is neither conciliatory nor belligerent about his past. Rather, he studies himself as we do, objectively positioning himself within the shifting political tides of recent Iranian history.

A Moment of Innocence is also Makhmalbaf’s most humanist film. There is little sign of the pugnacious ideologue of the early years, and nor is there a trace of the synthetic and ultimately futile attempts at visual poetry. His politics may not have mellowed but his approach to telling stories shows a newfound sensitivity. In the film’s magnificent final shot, the stabbing incident is spontaneously replaced with an exchange of a flowerpot with a loaf of bread between the two men. The actors, unbeknownst to each other, decide not to draw their weapons and instead offer each other a gift.

The final freeze frame has ironically become the most iconic image in Makhmalbaf’s career, though it is unrepresentative of his mode of filmmaking. It embodies both the English-language title of the film and the Persian one—translated as Bread and the Flowerpot—capturing a moment of innocence against a picture of two otherwise lifeless objects. It is an image in which the director’s stylistic strengths, the complexity of his political thinking and a hitherto unseen compassion toward his characters coalesced to produce a moment of genius.